North Queensland, Australia, is known for its ideal beaches. The beautiful scenery and tropical atmosphere of the area attract countless tourists and locals every year. Yet coastal waters are generally known for their potential danger as well. Throughout history, cases of injuries and fatalities resulting from encounters with dangerous wild animals have taken place, from shark attacks to envenomation from creatures such as stingrays. North Queensland’s beaches are no exception to these risks. However, sharks and stingrays are far from the region’s most urgent problems. The waters of Australia are often haunted by a nearly invisible killer which often causes beach closures. This marine hunter harbors extremely powerful venom which can kill a full grown human in mere minutes.[1] Its frightening killing ability has led it to become among the most notorious of all animals. To scientists, these creatures are known as cubozoans, but the general public knows them as box jellyfish.

Cubozoans received their name due to the square shapes of their bells. Despite their similar appearance to jellyfish (also known as scyphozoans), cubozoans are a separate class of animals.[2] Though both branches of marine hunters sport a primitive-seeming design, cubozoans are the more advanced of the two. These creatures can swim fairly fast, jetting at up to four knots through water. They also possess eyes, with a set consisting of six eyes located at each side of their bells (making for a total of four eye clusters).[3] These eyes allow them to see where they are going, as box jellyfish are known to maneuver around objects or animals which they find uninteresting or dangerous. Their tentacles are evenly spaced out in four sets, as well. Some of these traits make the cubozoans a very interesting and unique group of creatures, though many people react with fear to them rather than fascination. In reality, much of their reputation is due to just one species, a box jellyfish known as Chironex fleckeri, or the Australian sea wasp.[4]

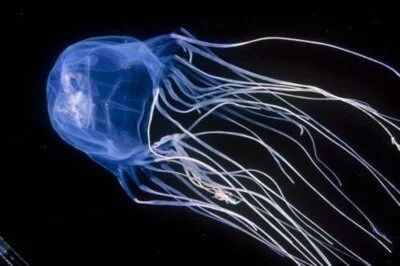

Possessing eyes, powerful venom, and near invisibility due to its transparent body, the Australian sea wasp is an incredibly effective marine predator. Photograph Credit: www.thinkquest.org

Like other members of the Cubozoa class, the sea wasp possesses a box-shaped bell when healthy. The bell’s diameter is usually between 16 and 24 centimeters, though the largest individuals have bells slightly over a foot in diameter. The bell is transparent, providing the animal with the camouflage it needs to easily close in on prey and remain hidden from potential predators (even these deadly creatures possess natural enemies). This box jellyfish’s hunting tools are its lethal tentacles, which dangle from its pedalia, or bell corners. Though the number of these tentacles can vary from individual to individual, a sea wasp can possess as many as 15 tentacles per pedalia for a possible total of up to 60 tentacles. These tentacles, which are usually of a blue-gray tint, can reach lengths of up to three meters. Its transparent body, long tentacles, powerful venom, and possession of eyes make sea wasps among the deadliest predators in the world. Interestingly enough, though box jellyfish have eyes and can clearly use them effectively, they lack actual brains.[5] This leaves scientists uncertain as to how the animals can process the information its eyes gather from its surroundings.[6]

This box jellyfish occurs in waters both in and around Australia and Southeast Asia. The species has also been observed inhabiting parts of the Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean, and the Great Barrier Reef. Box jellyfish populations are observed in the western coast of Australia, particularly from the Exmouth Gulf to Gladstone. It is the eastern gulf of Australia, however, that is best known for containing these creatures. This is due to the stings which many people have suffered in the coastal waters of Queensland throughout several decades.[7]

The sea wasp tends to inhabit the shallow and murky saline waters located near Australia, though the species usually relocates to deeper waters during storms in order to avoid being injured. These animals are also observed in freshwater rivers and mangrove channels during spawning. Young sea wasps will also inhabit shallow rivers during their polyp stage.[8]

The Australian sea wasp is not only the deadliest species of box jellyfish, but it is also considered the most venomous animal on earth. Photograph by David Doubilet/www.nationalgeographic.com

Like all other members of the phylum Cnidaria, which includes cubozoans, scyphozoans (jellyfish), anthozoans (corals and sea anemones), and other creatures, the sea wasp and its relatives have been endowed with specialized stinging cells known as nematocysts. The cells resemble capsules, and contain venomous barbs which are coiled inside of them during times of inactivity. In cubozoans, nematocysts are concentrated in rings on the animals tentacles. This allows for maximum contact when another creature touches a box jellyfish’s tentacles.[9] When a predator or prey comes into contact with the tentacles, chemicals on the outer layer of the animal’s body cause the rings to contract, triggering the stinging cells.[10] These cells immediately spring into action and fire the barbs contained within them. The barbs then penetrate the skin of the recipient creature and release venom into its body.[11] A sea wasp’s venom is extremely powerful and contains toxins which attack the heart, nervous system, and skin cells. The pain resulting from the venom’s effects is so overpowering that swimmers have been known to go into shock and drown or die of heart failure before even reaching the shore. Those who are fortunate enough to survive the venom’s initial effects and receive medical treatment quickly usually continue to suffer from great pains for weeks before fully recovering. The Australian sea wasp truly possesses a dangerous weapon at its disposal, and it is never in short supply; each of this box jellyfish’s tentacles can contain as many as 5000 stinging cells.[12]

Fortunately, humans are not actually targeted by box jellyfish. These cases are usually accidental in nature, with humans coming into contact with the stinging tentacles unintentionally as the box jellyfish attempts to swim around people. However, due to the animal’s transparent design, most people fail to notice it before being stung. In reality, these creatures rarely wish to come into contact with large organisms, as they possess soft bodies that can be easily damaged by large animals. Even small creatures can be potentially harmful to box jellyfish, and so they rely on powerful toxins to quickly incapacitate their prey.[13] These prey items include animals such as shrimp and small fish, which cubozoans frequently encounter throughout their environment.[14]

Yet even these deadly marine stingers are not free of predators. In fact, they are a favorite prey of many sea turtles, such as leatherback turtles and flatback turtles. These oceanic reptiles are unaffected by the stings of box jellyfish and regularly eat them as well as scyphozoans.[15]

Box jellyfish are common prey for certain species of sea turtles, such as this leatherback sea turtle. © Neil Osborne/www.seeturtles.org

The arrival of spring brings with it the sea wasp’s mating season. They begin their search for freshwater rivers, where they find their mates. Once the animals gather, they release their sperm and eggs into the water. Soon after this spawning, the adult box jellyfish expire.[16] The fertilized eggs hatch into planula, larvae which are pyriform (pear-shaped) in body shape. These planula larvae possess cilia, hair-like appendages which propel them through the water. They eventually attach into a hard surface and develop into polyps, the next stage in their life cycles. Cubozoan polyps can crawl around in their environment much like inchworms, gathering food into their mouths using the 24 tentacles which grow around their oral cavities.[17] They can actually bud off additional polyps as they continue through this stage. As the polyp develops into its final stage (the medusa), its 24 tentacles are absorbed back into its body and it grow four sets of new tentacles as well as four rhapolia (the sensory structures which house their eyes). Once this process concludes, the individual contracts repeatedly until it finally detaches and freely swims away.[18] The new medusa continues to feed and grow until it is ready to breed at the age of two months.[19] Thus is the life cycle of these fascinating animals.

Cubozoans have obtained a notorious reputation mainly due to the powerful venom of the Australian sea wasp. Recently discovered, this unique creature has captured the attention of scientists around the world due to their unique design and incredible killing ability. Possessing the most powerful venom on the planet and a transparent design which grants it near invisibility in the water, it is a hunter like no other. Though these characteristics have provided the sea wasp with much infamy, there is no malevolent purpose behind its design. It is simply a highly successful predator and survivor. It is the deadliest of marine killers.

[1] “Box Jellyfish – Sea Wasp Jellyfish.” www.jelyfishfacts.net. Available from http://www.jellyfishfacts.net/box-jellyfish.html. Internet; accessed 1 July 2011.

[2] “Introduction to Cubozoa: The Box Jellies!.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoa.html. Internet; accessed 3 July 2011.

[3] “Box Jellyfish .” www.animals.nationalgeographic.com. Available from http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/box-jellyfish.html. Internet; accessed 3 July 2011.

[4] “Introduction to Cubozoa: The Box Jellies!.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoa.html. Internet; accessed 3 July 2011.

[5] Schmidt, Timothy. “Chironex fleckeri .” www.animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Available from http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Chironex_fleckeri.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[6] “Box Jellyfish.” www.animals.nationalgeographic.com. Available from http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/box-jellyfish.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[7] Schmidt, Timothy. “Chironex fleckeri .” www.animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Available from http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Chironex_fleckeri.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[8] Ibid

[9] “Cubozoa: More on Morphology.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoamm.html#Nemat. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[10] “Box Jellyfish.” www.animals.nationalgeographic.com. Available from http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/box-jellyfish.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[11] “Cubozoa: More on Morphology.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoamm.html#Nemat. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[12] “Box Jellyfish.” www.animals.nationalgeographic.com. Available from http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/invertebrates/box-jellyfish.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[13] “Box jellyfish, Boxfish, Deadly sea wasp .” www.thinkquest.org. Available from http://library.thinkquest.org/C007974/2_1box.htm. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[14] “Box Jellyfish.” www.animal.discovery.com. Available from http://animal.discovery.com/fansites/wildkingdom/warrior/poll/bioweapon/bioweapon2.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[15] “What Sea Turtles Eat.” www.seeturtles.org. Available from http://www.seeturtles.org/1894/what-sea-turtles-eat.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[16] Schmidt, Timothy. “Chironex fleckeri .” www.animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Available from http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Chironex_fleckeri.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[17] “Cubozoa: More on Morphology.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoamm.html#Nemat. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[18] “Cubozoa: Life History and Ecology.” www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Available from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoalh.html#CuboLC. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

[19] Schmidt, Timothy. “Chironex fleckeri .” www.animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Available from http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Chironex_fleckeri.html. Internet; accessed 4 July 2011.

« Raw Speed and Beauty: The World of the Cheetah Dangerous Neighbors Part 2: African Lions and Spotted Hyenas »